Teach Better Series: Frames & Mechanics

Since the invention of the Internet, the popularity of polls and surveys have blossomed, most recently becoming fodder for click-bait and beyond. It becomes a “hook” to promote top 10 lists or what “most people believe” as readers surf the web looking for novelty, thereby stimulating various neurotransmitters.

One interesting set of polls performed are in reference to jobs or skills people believe they can do as well, if not better than “professionals.” A simple Google search will illustrate the point (although be careful of pop-ups and other potentially malicious things associated with these sites), but you might start to notice that one profession seems to be on those lists much of the time: TEACHING.

Poll takers refer to the allure of summers off (which is less true than ever before in K-20), the power of a captive audience, and no real-world experience being necessary for the position. However, another quick search of just how hard teaching can be might prove fruitful. An interesting opinion piece at Payscale.com showcases 8 reasons teaching is harder than you might suspect.

But at the end of the day, professors and instructors may just need a thick skin, noting that arm-chair quarterbacks abound in all aspects of life. As discussed in the previous blog, people have a natural tendency to believe they are good at all kinds of activities they are not truly good at. This ranges from professions like education to customer service to waiting tables, also including professional skills like communication or driving. Yet looking at the skill of communication, most CEO’s, business executives, and managers routinely suggest that communication is both a top need in hiring, while remaining one of the largest deficits for employees. Communication break downs hurt culture, impact sales, dilute brand, destroy collaboration, and on and on. In other words, people who believe themselves to be great communicators, are often not.

This blog series around how to teach better is designed to help professional educators find potentially new ideas as well as implement known concepts in new and unique ways. It is culled together from experts across various fields, but always filtered through a lens of best teaching by expert teachers. To that point, this blog’s topic of frame and mechanic are a perfect representation of just how hard it can be to truly teach another human being, while also showcasing the kind of work a professional educator must put in to be effective, if not great. Please note that the terms “frame” and “mechanic” are aggregator concepts. While underpinning works like How People Learn (2000), written by expert educators and expert scientists, engineers, and medical professionals do not use this terminology, they include several other terms which all fall under these topics. Unfortunately education does not have good synonyms for frame(work) and mechanic. (Goal and algorithm, context and objective, and other terms just do not capture the right sentiment.) So the terms, while not a staple in many education programs, are designed as umbrella concepts for this blog’s purpose.

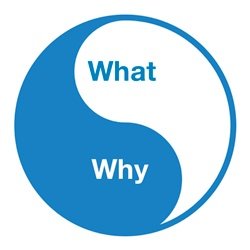

Beginning with mechanics, terms that might feed into this concept include practice, algorithms, objectives, sub-points, memorizing, time-on-task, etc. Mechanics are the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of learning. But mechanics are (by far) the easiest things to teach and also the easiest things to observe in teaching. Look for worksheets, flash cards, T/F or MC tests, bullet points, or other things to practice within a subject area to find the mechanics.

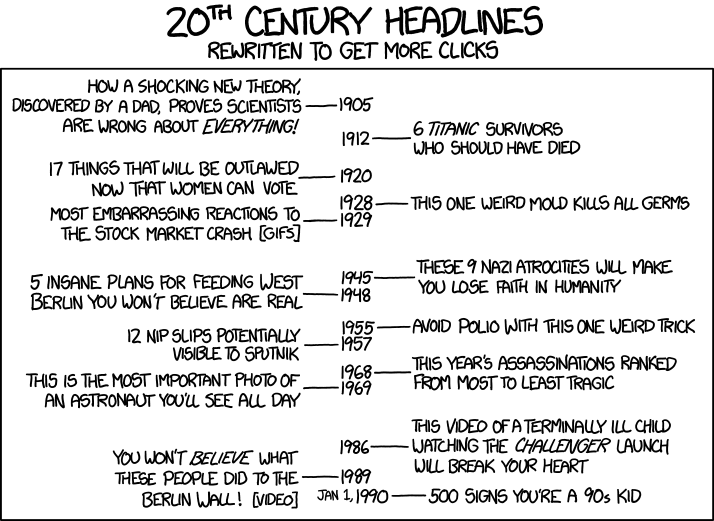

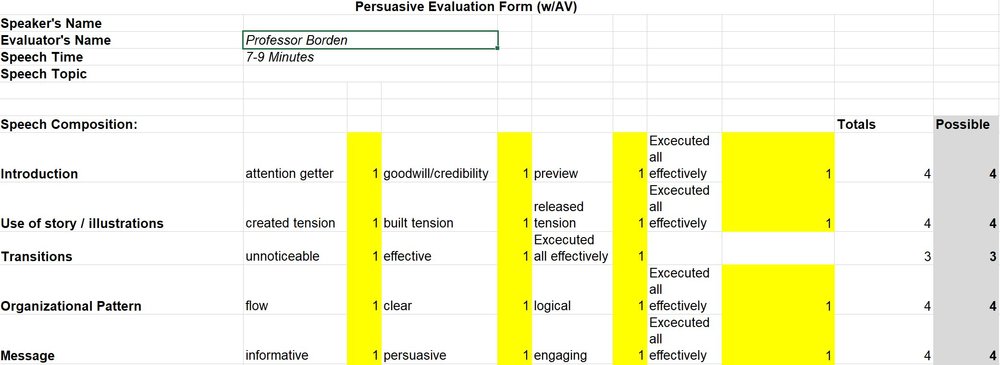

Mixing two commonly assumed expertise areas from above, look at how one might teach communication. There are dozens of mechanics within a speech: eye contact, vocal variety, reasoning, persuasive technique, temporal factors, proxemic usage, transitions, story, and about 90 more go into a “basic” public speaking rubric. Novices and arm-chair quarterbacks alike might tell you that effective public speaking is more a matter of “style” than objective (it is not). Experts who are not master-teachers (see the previous blog) can struggle with the mechanics because they don’t likely notice them anymore. They consistently use attention getters as a matter of course and they ensure a review is part of the conclusion without giving it much thought.

But master teachers use mechanics in various ways. Not only do master instructors turn seemingly subjective concepts into objective measures (like the need for at least 80% eye contact with an audience to promote trust and credibility), they also help students remember the mechanics WHILE supporting cross-reference to similar and non-similar, supporting concepts. Master teachers realize that practice assessments, flash cards, and other (potentially) gamified retrieval practices are learning tools, not just assessment tools (Make it Stick, 2015). Master professors ensure that students are not practicing mechanics in a massed / blocked way, focusing only on one topic at a time or solely covering one topic for a week, then moving onto topic two. Instead, through a spaced, intermittent fashion, master instructors are able to practice multiple concepts, variably over time. Again, sticking with the public speech example, a master educator will encourage students to practice transitions and conclusions as much as introductions, helping students overcome the natural tendency to practice the beginning of a speech upwards of 75% more than any other part of a speech.

The frame is decidedly harder. It is often harder to spot and likely harder to teach. Filtered through the Bloom’s lens, frame is a higher order skill than mechanic. Frame for our purposes means context, idea, “so what?”, reason, etc. If the mechanics are objectives, then the frame is the outcome or potentially the goal. If mechanics are the how and what, frame is the why, with shades of when and where.

Sticking with our public speaking example, frames are a filter or lens by which to ensure the mechanics work appropriately. The big ideas a speaker should use to inform a speech include audience analysis, perception vs reality, Aristotle’s underpinnings of ethos (credibility) / pathos (emotion) / logos (logic) / and mythos (story), informing vs persuading vs speaking ceremonially, and more.

It is important to note that there is not necessarily a 1 to 1 relationship, but instead a healthy amount of overlapping and intertwining. Perhaps in specific science or math examples, but even then, there are likely multiple frames and shared mechanics across frames. In our example here, simply knowing the frame of Aristotle’s Canons would certainly be better than no frame at all, but not nearly as powerful as dovetailing it with audience analysis and more, with various mechanics feeding both umbrella concepts. In other words, if you were to concept map it, there would be a lot of crossing lines, differentiated colors, and shared circles.

Master teachers ensure that novices are changing strategy or direction for an upcoming presentation based on the audience in the room, how much internal credibility the speaker has, and whether examples should be emotional narratives more than logical video clips. Novices typically do not filter by a larger frame at all and expert (non-master) teachers unconsciously change style and format for the situation at hand, but struggle to explain this to students.

It’s hard to completely see frame vs mechanic at work, but think of it this way. Trying to be apolitical, see if you can look at the following solely from a public speaking perspective:

- Good at mechanics, less so at frame: George Bush Sr., Hillary Clinton, Mitt Romney, Al Gore

- Good at frame, less so at mechanics: Jimmy Carter, Donald Trump, George W. Bush, Ted Kennedy

- Good at frame AND good at mechanics: Ronald Regan, Bill Clinton, Paul Ryan, Barack Obama

While no person is the same in every situation, every time, these politicians have a decent body of work to draw from. Hopefully it helps exemplify usage of either mechanic, or frame, or both within our communication example.

If you are a master teacher (one way to tell is whether or not you read this entire piece and are now looking up the links, seeking more information, and personalizing the concepts…) you are now likely working to determine your frames and mechanics. They live on a continuum as sometimes a concept can be fitted into both categories (which is a very high level way of thinking, by the way). Identification of frames and mechanics should be part of the strategy for students, although identification alone is a lower-level skill and should not be weighted very heavily. But ideally, every mechanic fits within a frame and every frame has a list of associated mechanics.

The next blog in the series will discuss how to teach concepts in a state of disequilibrium and why trying to make learning “easy” is typically the wrong approach. But until then, deconstructing your important concepts into frames and mechanics is a crucial step in curriculum management AND better teaching.

Good luck and good learning.