Teach Better Series: Neurotransmitters (The Goldilocks Chemical)

* Blockchain * Brains * Clickbait *

Did any of these terms peak your interest? The three concepts (above) have actually been shown to increase website traffic, purchases, and attention in extremely dramatic ways. On-Line Plc (a British company) changed its name to ‘Blockchain’ and saw shares skyrocket upwards by 394%. People are more likely to believe findings from a neuroscience study when the report is paired with a colored image of a brain as opposed to other representational images of data such as bar graphs, according to a new study from Colorado State University. Newspaper readers are also far more likely to read a piece with a brain image than the exact same piece without. Clickbait has seen some click-thru rates on Facebook and sporting sites in the tens of millions.

What does all of this have in common? Neurotransmitters.

Brain images lead audiences to read articles and find them to have greater validity

Brain images lead audiences to read articles and find them to have greater validity

“Pitch Anything,” by Oren Klaff is a mix of communication, persuasion, sales, marketing, filtered through a lens of brain science. It is not an education book per se, but it does touch on these points from the perspective of how we motivate, grab attention, and speak to human audiences (whether students or otherwise). When dovetailed with more academic works like Brain Rules (Medina, 2006), Make It Stick (Brown, Roediger, McDaniel, 2015), How People Learn (Bransford, 2000), and Drive (Pink, 2011), one starts to gain a better understanding of how neurotransmitters impact the brain, and therefore impact learning.

In the last blog from this series, we examined the notion of a Goldilocks concept being “just right”, while we also explored potentially “too hot / too cold” neurotransmitters in glutamate and cortisol. Now let us explore four brain chemicals that can create a strong chemical cocktail for learning, especially when used together.

Let us start with serotonin. At first glance it may appear that serotonin is very difficult to influence in a student population. Serotonin is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that has been found to be directly related to emotion and mood, ultimately regulated by sleep, nutrition, fitness, and other life factors. Too little serotonin has been shown to lead to problems with anger, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and even suicide. Too little may also lead to an increased desire for carbohydrates and trouble sleeping, which can create a loop of depression and other emotional disorders.

While sleep, healthy eating, exercise and other serotonin-inducing behaviors may not be within an educator’s control, and until policy makers and administrators actually push for changes that encourage serotonin-related student success efforts (like learning experiences based on the time of day people learn best vs forced class times, or erasing the notion that time equals learning at all…), try to set your class (and yourself) up for as much success as possible. Ideal learning times (for the widest swath of population) are 10:30am – 2pm, based on natural serotonin fluctuations (which can be connected to circadian rhythms, etc). As well, limit other negative neurotransmitter influences like sugar substitutes, MSG, casein (cheeses), which can spike the system with glutamate, the toxic, neuron killer that inhibits learning and memory. Inform students, parents, other professors, administrators and the like about the influence of this regulating hormone, potentially even creating curriculum to help learners understand the value of stasis.

While serotonin may be augmented and supported through ancillary means, the last three chemicals in this cocktail can be influenced directly. The next synaptic response is described by Mr. Klaff (who is not a scientist, but rather an aggregator / relator of findings) as the ‘cocktail of attention’ consisting of two crucial brain chemicals. Dopamine and norepinephrine should be a filter for architects of learning, both separately and also together.

Norepinephrine can be described as the chemical that occurs when a person feel disequilibrium, tension, or conflict. Note, it does not have to be negative emotionally, but when a person feels a compelling question, a challenge, or some other discomfort that simply must be resolved, norepinephrine is at work. Too much norepinephrine creates anxiety, leading to glutamate over-production. Too little norepinephrine creates boredom, leading to cortisol flooding the system. But the Goldilocks notion of norepinephrine is just right for students who continue working toward an answer.

Dopamine might best be described as the, “you can do it” hormone. Dopamine is not associated with the excitement of getting a reward, but of anticipating said reward. Dopamine’s release feels desirable to people as it associates with feelings of ability or obtainability. This is, “the thrill of the hunt,” people describe. Dopamine is often seen in people exercising as they push toward a goal, time, or finish line.

But Klatch brings these two chemicals together in a practical state, surmising that when a person is feeling both desire and tension, that person is paying (genuine) attention. Want to give a dopamine kick and create desire in students? Offer a reward. Want to give a norepinephrine kick and create tension? Try taking something away, creating a challenge that is hard but obtainable, noting a problem worth fixing, etc.

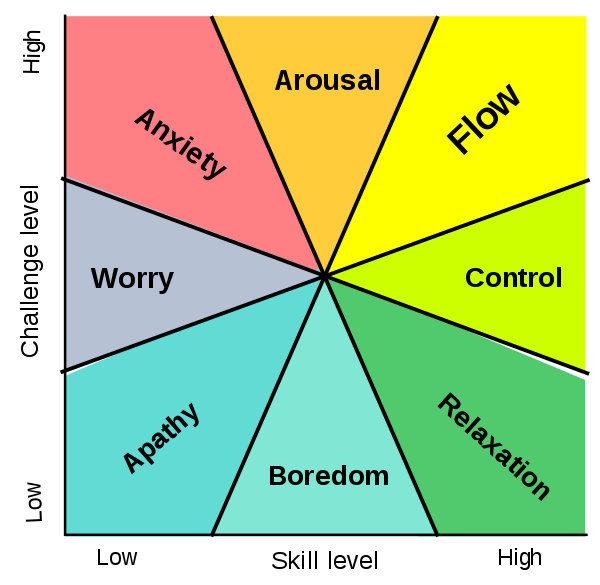

So how do educators promote that cocktail in a student’s system and gain / keep attention? Novelty. The human brain is stimulated by surprise because our world is fundamentally unpredictable. This is why television viewing, gaming, and web surfing are so pleasing to the human brain. These activities represent minute after minute of motion based, new, and interesting (although not fear-inducing) information. So, great teachers or presenters create novelty by violating the audience’s expectations in a pleasing way. Novelty in the form of an unexpected gain gives the brain a blast of dopamine. On the other hand, if an anticipated reward is too hard. leading to ‘rage-quit’ by the learner, glutamate takes over. Similarly, if the reward never comes to fruition, then dopamine goes away, and negative feelings begin to creep in. Likewise, novelty in the form of a problem deemed too complex to even attempt does not produce norepinephrine, but cortisol instead, changing the cocktail from attention to boredom. This is why “gamified” experiences of simply adding points or scores to a learning experience are likely described by Karl Kapp (The Gamification of Learning and Instruction, 2012) as the least interesting part of a game. These components do not make a game, but rather conflict, challenge, and skill make up a game. Likewise, educators who create “flow” (Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, 2010), which is just enough challenge requiring just enough skill, enter the Goldilock’s zone of learning, seeing students who are both motivated and even find that learning time “flies by.”

Which leads to the Goldilocks neurotransmitter in the ultimate learning cocktail: endorphins. Endorphins (short for “endogenous morphine”) are structurally very similar to opioids (opium, morphine, heroin, etc.) and act similarly. (Opioid drugs literally work by attaching to endorphin’s receptor sites.) Endorphins impact pain reduction and pleasure.

But endorphins can be wrapped around cognitive activities as well. Spikes of endorphin release can be seen when attaining the reward promised (dopamine), through triumph associated with strenuous physical activity, when a challenge (norepinephrine) has been overcome, or a puzzle has been assembled. In fact, pattern finding (vs problem solving) leads to an almost perfect chemical cocktail with fMRI and PET scans illustrating the release of norepinephrine, dopamine, and endorphins all within a single experience.

Stated as pragmatically as possible, norepinephrine, dopamine, and endorphin creation by students means classroom presentations, educational experiences, and learning architecture should be facilitated puzzles, gamified experiences, or flow-inducing moments. Audience-centric problems, punctuated by tension building narrative, woven around focus shifting boredom busters should result in audiences assembling the pattern on their own – not manufactured the facilitator – in order to achieve maximum retention, connection, and ultimately, learning.

In our final blog in the Teach Better series, we will wrap up with an umbrella term: Active Learning. We will look at what is, what is not, and why defining active learning is both difficult but important.

Good luck and good learning.