Teach Better Series: Conclusion

Attention Blindness – Confirmation Bias – Prospect Theory – Active Learning

How does one know what they don’t know? Is your approach to a problem the best approach to a problem? Can we be too focused?

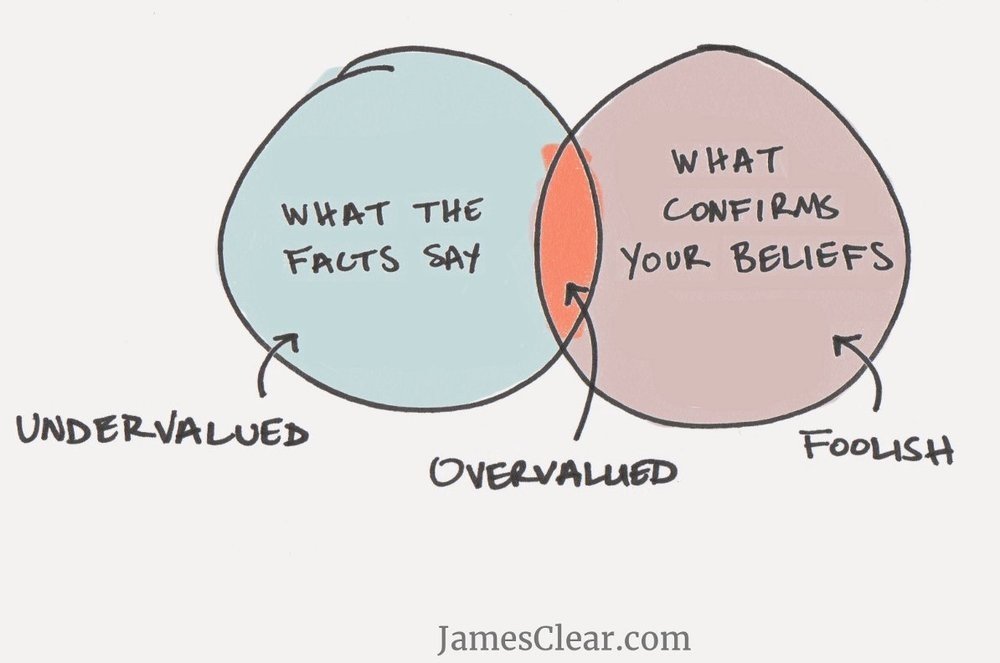

“What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact.” –Warren Buffet

As noted previously in this series, human beings tend to believe that they know better than most, act better than most, and think better than most. Likewise, Nobel Prize winning authors of books like “Nudge (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008)” describe prospect theory, another Nobel prize winning theory by Daniel Kahneman, which explains (among other things) that humans are very bad at inferential statistics. People tend to make decisions, even extremely important ones around money, family, or even legality, based on emotional values more than scientific, predictive values. This is true of everyone, including statisticians. Humans over-weight small probabilities to the point of influence on a consistent basis.

Practically stated, people will avoid known losses to optimize for certain wins due to the pain associated with loss, even if those losses would lead to greater wins in the end. Or through another lens, most people would take $50 (guaranteed) over a 90% chance of receiving $100, due to factors like uncertainty and risk aversion. Another seemingly extreme example exacerbated by outside sources (like the 24 hours news cycle reporting predatory stories with great regularity), a mother might easily believe there is a pedophile in every neighborhood household, reinforcing their belief that no place in the world is safe for their child.

Cathy N Davidson adds to this conversation in the book, “Now You See It (2012)” as she describes attention blindness. Attention blindness can be considered both a cognitive science as well as a cognitive psychology issue, whereby people focus intently on one thing, while being “blind” to other things. Our brains need to work this way or sensory overload would prevent productivity. Yet, as Davidson points out, attention blindness can be seriously limiting in our ability to solve complex problems, collaborate with others while avoiding group-think, even think critically.

Which is all a setup for the final Teach Better Series concept of Active Learning. At the heart of this series is an assumption, if not an earnest question. What is active learning? Does confirmation bias cloud our judgment regarding this crucial issue? Do we struggle with prospect theory, over-weighting small measures as we evaluate the engagement level of students? Is our attention blindness of subject matter clouding our ability to note meaningful interaction between the students and the topic? While this question can be answered quickly, if not dismissively, it is an important question to answer thoughtfully, from a learning perspective. But an answer may be harder to find than one might think as there is little community agreement from the teaching profession regarding how to answer this question. Ambiguity surrounds the notion of active learning.

A simple Google query for this question will result in almost 200 million hits, with the top result defining active learning as any instructional method which “engages” learners. So, an already amorphous concept contains an equally ambiguous term like ‘engagement’.

Platforms such as LinkedIn or Twitter see more disparity. @tjoosten (a seasoned educator, researcher, and the Director of Digital Learning across the University of Wisconsin system) asks her vast network to define and explain active learning. She facilitates several social media conversations asking if digital learning is active by nature? How is active learning defined, what is the theoretical underpinning behind it, and what is an appropriate methodological approach? The answers are varied, including shallow, deep, narrow, and wide responses.

Publishers, societies, and consortia alike answer the question differently. Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching expresses active learning as something that creates excitement in the classroom. (Yet failing to explain how excitement is measured.) The University of Nebraska’s graduate connections site suggests, “Anything that involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing” is a form of active learning.”

What should readers of the Teach Better Series take away regarding active learning? We believe two things matter. First, regarding attention blindness, confirmation bias, and prospect theory, the best educators realize that expertise in active learning suggests the more we know, the more we should realize the less we know. No master teacher gets it right every time. The variables of students, background, subject matter, and hundreds of other things mean active learning must be dealt with uniquely, contextually. While scale is achievable and measurement is possible, architects of active learning should likely marry the most effective practices from both learning-science based teaching as well as curriculum, but including non-cognitive strategies too.

The second thing this series has tried to illuminate, is how to start defining active learning. If it is true that active learning is a frame, then (as this Teach Better Series suggests) frames are made up of mechanics. Active learning is the (hard to measure) goal, but the outcomes or potentially objectives (which are far easier to measure) include crucial concepts like desirable difficulties, chemical cocktails, and disequilibrium. Expert practitioners like Dan Meyer, Gordon Sanson, and Chris Dede all approach active learning uniquely, but their mechanics apply to the brain science of gamification, the “do first” notion of generative learning, the learning catalyst of a truly compelling question, and more. Active learning mechanics were even leveraged by Derek Muller, whose PhD dissertation asked what it takes to create an “engaging” learning video, which became the basis for Veritasium, a YouTube channel dedicated to science videos.

So, while active learning is not necessarily easy to define, it is not difficult to see, nor even hear. (A classroom sounding more like a coffee shop than a library might be a lighthouse signal of active learning.) Regardless of how easy active learning is to measure, the parts that make up the whole can be intentionally, strategically leveraged in any learning context.

This Teach Better Series hopes to bring some new concepts to the conversation of teaching and learning. Intentional, pro-active use of cognitive science, learning research, and effective practices in education technology should help master teachers produce remarkable results. We trust you have a heaping helping of summer reading for the next few years. But as we finish, here are two parting thoughts to consider.

First, ‘master instruction’ or perhaps better framed as learning architecture is not easy. The old adage of “those who cannot do, teach” is simply not accurate. Those who ‘cannot do’ might very well be able to talk or lecture or drone on…but they likely cannot teach. Teaching implies learning and learning is very complex, indeed. Master teachers are always on the lookout for new ways to conceptualize, new methods by which to make things clear, and better ways to make learning stick. (But this never-ending journey is highly rewarding when staying on the path.)

The second important concept to remember is that the more these mechanics and frames are leveraged, the easier they are to use. Just like any human activity, the more you do something, the easier it becomes to see, deconstruct, strategize, and implement. As noted, interleaving is a great example of this. In many classrooms interleaving, which has been rigorously shown to be a better learning design strategy, is very uncomfortable for both learners and practitioners at first. It simply “feels wrong” initially. But, if a master teacher commits to the strategy (based on the overwhelming evidence of its effectiveness), eventually they will see its efficacy, which will likely soon translate to students as well. What was frustration will turn to habit which in turn can become efficiency, if not innovation. But just like our students, we must give ourselves time to experiment, practice, revise, gain feedback, and fail. Perhaps at the end of the day, that is how to best “define” active learning, both for the teacher and for the student.

We hope you have enjoyed this Teach Better series. Please feel free to share any of the ideas or concepts with your colleagues or other practitioners you may come across. In the never-ending quest for student success, we hope the ideas and techniques described here will inspire you as an educator but also that you will find them to be nice additions to your teaching toolkit.

Good luck and good learning.