Teach Better Series: Neurotransmitter

Can the Earth hold 10 Billion people?

It is a valuable conversation to be having right now, especially as scientists, economists, nutritionists, climatologists, and other experts suggest our planet and our people are going to struggle as we get closer and closer to that number. Water, food, land, pollution, supply, demand, fuel, and many more issues are magnified with every new person on Earth. While some countries are seeing fewer babies born in the past decade (the USA), some countries have more than made up for the downturn. (There are some countries in the world where the average woman has 6-7 children.)

As a result, some are looking to the heavens. Beyond Elon Musk (who is guarded with his reasons for a Mars colony, but has eluded to everything from World War III to planet killing asteroids), there are those who wonder how the human race will not just survive, but thrive. Earth II may sound more like a movie than our reality, but several organizations, including NASA are looking for another Goldilocks planet to call home.

What does that have to do with teaching and learning? It’s a fair question, but read one last paragraph about the concept and see if it starts to become clearer.

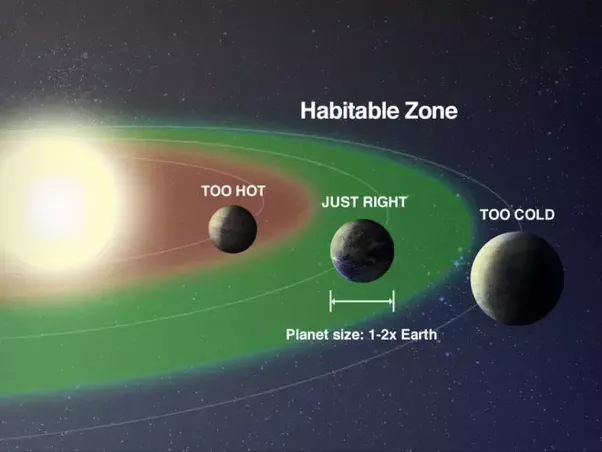

A Goldilocks planet is a planet that falls within a star’s habitable zone, and the name is often specifically used for planets close to the size of Earth. From the classic tale of the three bears, the concept is simple enough. Find porridge that is not too hot, nor too cold. The same thing applies to planet hunting. A Goldilocks planet is one that is neither too close nor too far from a star to rule out liquid water on its surface and thus life (as humans understand it) on the planet. Obviously, the planet has to be amenable to hold oxygen, sustain plant and animal life, and other necessitates for human existence. So, researchers scour the universe with probes, super telescopes, and other tools to find such a planet. So far, after looking at (literally) billions of planets, scientists believe they have a list of 219 possibilities, the closest being a mere 40 light years away (235 trillion miles).

If you still have not guessed what this has to do with learning, consider this. The number of variables associated with finding a new planet are numerous. Just one “bad” variable and the whole search would be called off. Yet, look at learning from the same mathematical perspective. How many variables are involved in truly learning something? Thousands? Millions? More? And any single variable might derail the learning process at any time, proving too hot or too cold. Hunger, depression, dehydration, lack of scaffolding, and on and on are all potential education killers.

This series has already examined several context-based ways to create a learning rich paradigm. But if one looks beyond the learning environment, on a brain-chemical level for instance, far more variables are created. From a chemical perspective, the next blog in the series will illustrate how to create a desirable “chemical cocktail” for learners. But we should also note ways to (hopefully) avoid negative synaptic experiences. Here are two neurotransmitters that could easily qualify as “too hot” or “too cold” for learners.

Glutamate: It is important to state that neuroscientists really struggle to agree on much of anything. While this likely suggests non-brain scientists should take serious note of any concepts that happen to be agreed upon, it makes things very frustrating if you are seeking brain-based recommendations for students. These next two blogs will try to speak to (mostly) agreed upon ideas from the cognitive science realm. Glutamate is an example of this.

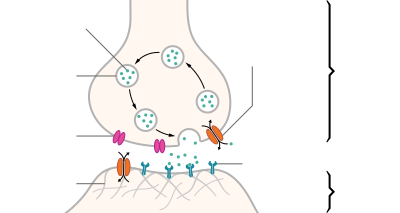

First, it must be stated that glutamate is crucial to brain function. In an over-simplified description, glutamate is part of the central nervous system and is called an excitatory neuron. As the main excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate sends signals to the brain supporting cognitive function, memory, learning, and more. So why would we want to avoid glutamate as an educator?

It’s not avoidance of glutamate, as much as the avoidance of too much glutamate. This neurotransmitter definitely falls into the category of “too much of a good thing…” When glutamate is created in large doses, it does not act like grease for your brain’s engine, but instead seriously disrupts it. Glutamate, during times of crisis or high anxiety, literally launches out of the spinal column so as to “eat” neurons. Why? Most scientists believe this is one way our brains protect us. If a bear is charging you in the woods, you do not need your neurons firing around why that is happening. You just need to run! Glutamate helps you act, instead of thinking too much.

Can you see the dilemma with high anxiety issues like testing, performances, or other high-stakes experiences? We literally must desensitize ourselves to those situational contexts, thereby taking the anxiety out of the equation if we want to perform effectively. If not, we can likely have our own systems start “eating” the neurons which we need in order to process, recall, or apply. Simply adding a potential “major” penalty to an assessment can make a competent person fail.

But things aside from penalties can bring on anxiety. Feelings of being alone or overly unique can make some people feel anxious. Bullying, self-esteem, lack of mindset, lack of friendships, lack of networks, and more can lead people to become overwhelmed and anxious, thereby making functional learning very difficult.

So, creating experiences that promote socialness, affirming people as respected, likable, and capable, while also allowing for collaborative, positive outcomes can make all the difference in the world.

Cortisol: You have likely heard of Cortisol. Time, Newsweek, and others have reported on this “stress” hormone as a significant health risk, potentially leading to premature death. Studies have shown that cortisol can be “contagious” as students feel more stress when teachers are burned out. In education contexts, Cortisol can be quickly created by criticism, grades without meaningful feedback, and even boredom, flooding the system with the desire to oversleep / under-sleep, over-eat / under-eat, and other depressed exhibitions.

Boredom, while hard to extrapolate to everyone, essentially stems from a lack of engagement, motivation, or connection. It may be difficult to say what causes boredom for every student, as people are so different. But rather than taking a defensive posture around this serious issue, going on the offensive might be a better strategy. Varied learning, sometimes thought of as differentiated, individualized, or even personalized learning offers a great deal of promise against bored students.

While there are dozens of examples, there are various themes within varied learning that should be viewed as a filter for every learning context. The amount of time spent on any single activity should be intentional; fluctuating approaches to tell, show, do, review, and ask moment should be done with purpose; helping students work through mechanics by which to determine frames, surrounded by support and praise should be part of most workflows.

Educators definitely want to stay away from bad chemical cocktails like glutamate and cortisol if possible. With strategies in place, as well as knowledge regarding how these neurotransmitters work and (more importantly) how to avoid them, we can create learning experiences that help students get the most out of their brains.

The next blog in the series will look at those Goldilocks hormones and how they can help students achieve success.

Good luck and good learning.